5 Forces That Can Make You a Business Writing Bore

Chris Gillespie | July 26, 2024

If you’ve spent any amount of time in an office, you’ve encountered passages like the one below that are so empty they verge on performance art.

“We expect competition for assets to intensify as leading companies reevaluate their priorities and overcome core challenges by focusing on experimentation, strategy maturation, and value upliftment.”

Or vaguely sinister pronouncements.

“The profits were realized.”

Or this flashmob of hyperbole.

“Stop!!! The wrong agency can KILL your DTC but the right one can skyrocket it up to an 11.”

Or this pre-webinar wall of legalese.

What is true of all of these statements? They are all, essentially, meaningless. They are words, yes, but absent of any communication. (Beyond the sometimes violent gesticulating.) It’s TV static. A podcast with no sound. A message in a bottle that turns up blank. There is nothing for us to decode or act upon.

And they aren’t ill-meaning—I believe those authors had the best intentions—they were simply subject to the five forces of unclarity which exert a gravitational pull to keep business writing empty.

Let’s learn those five forces, and how to thwart them. We’l then apply each lesson to a piece of writing above. (And if you find this fun and useful, know that we teach a course on it.)

1. Abstraction: Companies aren’t real and often defy description

Companies are difficult to write about because they do not exist. Not in any material sense. For example, if I asked you to go touch Google, how would you do it? Slap a building? Hug a server? Lock arms with an engineer? And if you tried all that and even stole those resources away from the company, would that company still exist? Certainly so. It’s omnipresent, yet it is nowhere. You can only make out its silhouette. Companies are monolithic legal abstractions.

This was always their purpose, going back to their origin as joint stock companies. They were invented to defray responsibility and place any liability upon a non-person entity. (Readers of Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens are chuckling and nodding.)

That makes companies a pretty abstract concept—adults collectively hallucinating that a non-person entity governs their time. Abstract concepts like this are difficult to describe—not unlike dreams. And abstract concepts that produce abstractions such as strategies, decisions, visions, memoranda, processes, positions, and the like, are a mess to explain.

Trying to describe abstract work situations makes clear that our language—invented and organized during long centuries of physical labor—is comically antiquated (and surprisingly offensive). It’s why most work documents strut about as if attired for a Renaissance festival:

Circling wagons

Holding down the fort

Irons in the fire

Running campaigns

Spinning flywheels

Kicking off projects

Striking while irons are hot

Giving people free rein

Contacting upstream suppliers

Keeping things above board

Keeping investments afloat

Digging a competitive moat

Raising a red flag

Quite simply, people are stuck applying the language of physical form to situations that are, in more ways than one, mental.

To fight abstraction, be more specific.

2. Insincerity: You’re often punished for telling the truth at work

Work is politics and sometimes, the truth will offend your boss. Or incense a partner. Or, naming the source of your team’s dysfunction would only inflame the situation and immiserate others. As a kindness, people learn to veil the truth in a style of writing called “passive voice” wherein they demote or remove the subject, so it’s as if the action just occurred spontaneously—like swamp gas.

For example, they say, “People were let go” to not name the firer. Or they announce, “A shortfall was experienced” because it makes that shortfall less clearly someone’s fault.

Then they bury it in further euphemism by declaring, “There was a right-sizing” because phrasing it this way protects the right-sizer and obscures the real meaning, which is “someone fired our coworkers to cut costs.”

No matter the motive, passivity is always at odds with clarity. It's difficult to read because that’s the point. A clearer telling would be impolitic.

It doesn't have to be the case—there are always clearer alternatives—but wherever workplaces don't make it safe to speak honestly, passive voice is used. (Ick, it pained me to write that.)

To fight insincerity, be brave and say what you mean.

3. Rush: People are too busy to understand or explain

Putting words to paper is easy. Reorganizing them to benefit your reader takes time. Anywhere you see a billowing smokescreen of buzzwords, jargon, and cliché, you’re probably seeing a well-meaning person in a rush.

Trouble is, when people are consistently rushed, they start to confuse having written something with being understood. But these are not the same. The message sent is only as good as the message received. And sometimes, there’s little to receive. For example, this gem:

“By the way, the on-brand execution of best practices tailored to your unique audience is what leads to the best execution.”

I’m sure there’s meaning in there. But can you find it? I cannot. It is circular. The author neglected to ask, “Will others grasp my meaning?” They were probably in a rush. As the author William Zinsser put it in his book On Writing Well, “Sloppy editing is common in newspapers, often for lack of time, and writers who use clichés often work for editors who have seen so many clichés that they no longer even recognize them.”

To compound this, if written by an expert, this may be the clearest they can get, for they know so much, their knowledge becomes a curse. They forget what it’s like to not know. When they read the phrase “best practices,” a curtain rises and they see a diorama of associations and meaning. But for the rest of us, we just see the speaker gazing absently into space.

Never assume others will understand. Because it doesn’t matter how smart we are. It matters what our reader takes away.

To avoid rushing, slow down.

4. Pretension: People fear they’ll be dismissed if they use simple words

It’s not uncommon for my clients to unclarify their own writing. When asked to edit, they change the perfectly serviceable “This helped” into “This relentless focus on value elaboration ensured transparency and accountability for every element of the transformation.”

I’ve learned not to take these edits personally. I think they’re actually easier for folks to write. This is how they think about it. But there’s no question this abstracts the writing and increases the difficulty. Even for readers within their own industry.

That’s because the more abstraction, the more cognitive effort it takes to read, and the greater the chance for miscommunication. If someone says “let’s circle back on profit enhancement,” both professionals may nod and leave with completely different views.

And yet if you simplify things to a level that others can actually understand, these types of clients recoil, as if you’re asking them to streak through the lobby naked. They quickly reclothe it in layers of ornamental words. Why? I call it plainophobia. They fear that simple words make them sound simple. But simple doesn’t mean dumb. It means clear to others.

Just have a look for yourself at your favorite nonfiction authors, or the writers most celebrated in your industry. You’ll find their language is quite simple and direct. Often at an eighth-grade reading level. Match that.

To not sound pretentious, be more precise.

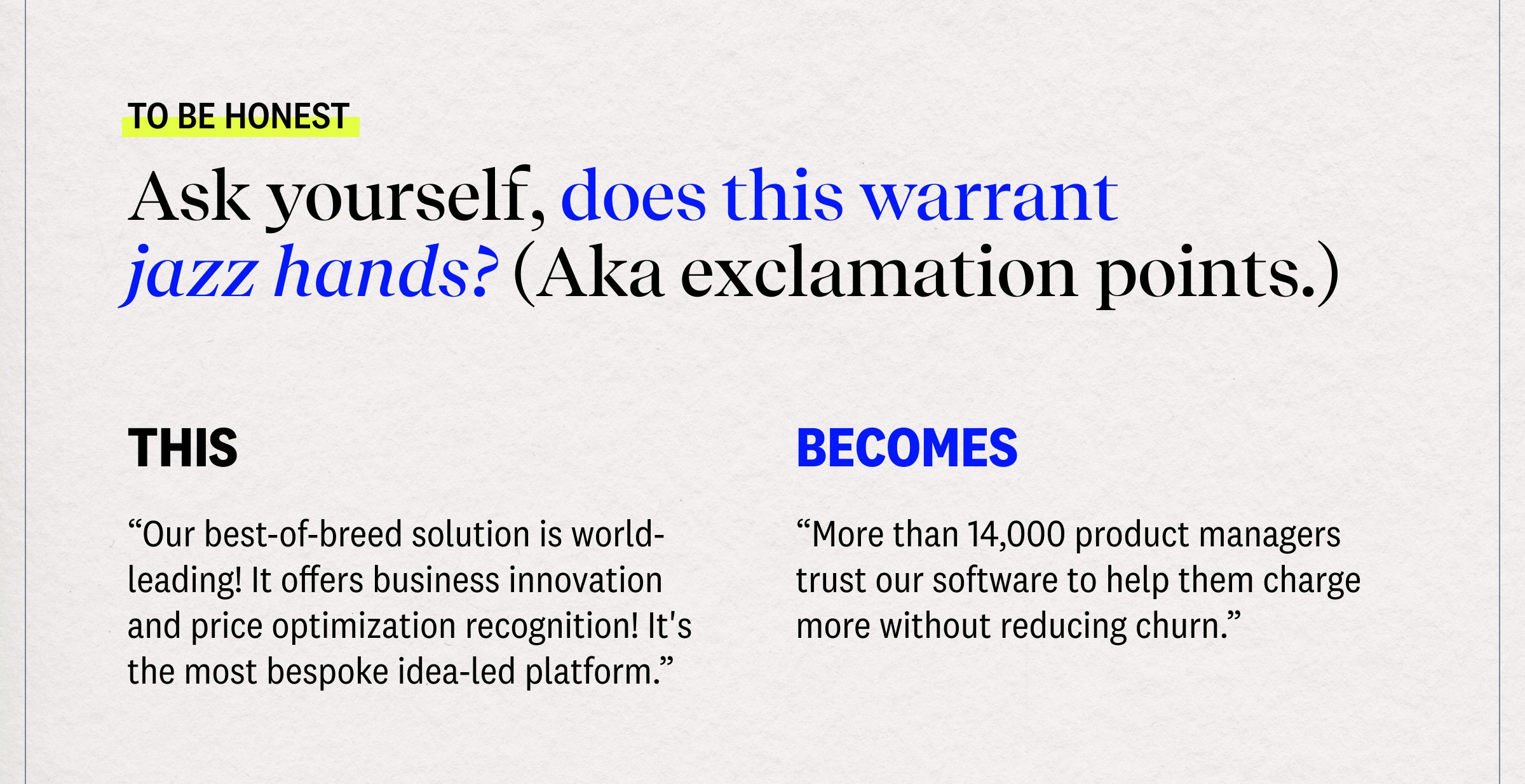

5. Bombast: People think bombastic language sounds smarter than it does

Sometimes, people who’ve written something plain fear it will make them look unsophisticated. Or that it doesn’t convey their proper level of excitement about the topic. So they tack on unnecessary ornamentation:

A “best of breed” here

A “world-leading” there

An extra “business"

An exclamation point

A second exclamation point

Insert an “amazingly”

Stuff in a “solution”

Puff up verbs with "-ization"

This is how you get a phrase like the following, so hollow you can hear the echo:

“Our best-of-breed solution is world-leading! It offers business innovation and price optimization recognition! It's the most bespoke thought leadership-led platform.”

Readers subconsciously understand this deceit and back away.

The fix? Be rid of all ornamentation. If the product or message is good, it’ll be even more so without this cruft. The trouble is, in all that stripping away, there's a chance there isn't anything left. Just scraps and deflated claims. But that’s a product problem.

Marketing can’t help you with that.

To write clearer in business? Ask better questions

Aim to be precise, concise, and easy for others to understand at a glance. That’s what it takes to communicate effectively. People should feel themselves pulled into your writing by force of the ideas. But they can’t get at those ideas if your writing is suffering from the five forces: abstraction, insincerity, rush, pretension, and bombast.

There are countless good books that can help: On Writing Well by William Zinsser, Sense of Style by Stephen Pinker, and Everybody Writes by Ann Handlely.

You can also play a game we at Fenwick developed called Lingo Bingo, which is bingo, but for business jargon. You can play it on companies’ websites. (Here’s the board.)

Or you might also be interested in this course we built. After 10 years and hundreds of client projects, we’ve developed a method for writing in which you learn to continuously ask yourself three questions to be rid of these forces forever.

If you found these lessons useful, you’ll likely love our course, Think Like A Writer.