Report 3 | Nov 2, 2025 | Get these in your inbox →

The first time I learned that San Francisco gets most of its drinking water from a slender pipe assembled in 1921 running out to Yosemite—which is partially wooden and sometimes bursts, sending 40-foot plumes of snowmelt through farmers’ fields—I did two things:

- Solemnly stocked emergency water in our basement

- Purchased more books on the subject

Infrastructure is something I’ve thought about a lot lately. Seeing people living on islands, I now wonder, where do they get electricity? Send sewage? Pipe in fresh water? You have to wonder about the internet too. How does an email get from Brussels to Taipei? (The answer is 900,000 miles of garden hose-sized undersea cables.)

In this issue, I take a trip to Hetch Hetchy with a few architect friends to marvel at the immensity of a grand public works project that is that dam—San Francisco's proverbial headwaters. And also reflect on a nation that once dared like this but no longer does, and realize I’ve been called by the song of the protesters who tried to stop it.

A second Yosemite

The trip began as so many do now, with me trying to tie off work before losing cell service. We three sat in Groveland, CA, at dusk, on park benches, eating burritos—me one hand on a laptop proofing the prior issue of this newsletter. We’d secured permits, but on account of the government shutdown, didn’t bother to pick them up. I slammed the laptop shut and we sped to the backpacker’s campground to get some rest.

On that drive we talked about big public works projects that once defined this country. From the 1930s to the 1960s, the U.S. went on a building spree designed to lift us out of the depression. Those artifacts became what we now think of as America—280,000 miles of road, rest stops, courthouses, and schools. But as Ezra Klein covers in his divisive new book, it’s become hard to build, as my friends, the architects, confirmed. Permitting can take years even when no studies are involved; my friends described petty tyrant bureaucrats they’d met, and labyrinthine paperwork. At the same time, at least some of those regulations are well-meaning. Something like a dam over the wonderful valley that was Hetch Hetchy could only have occurred when it did—before an environmental movement or any care for native people’s rights.

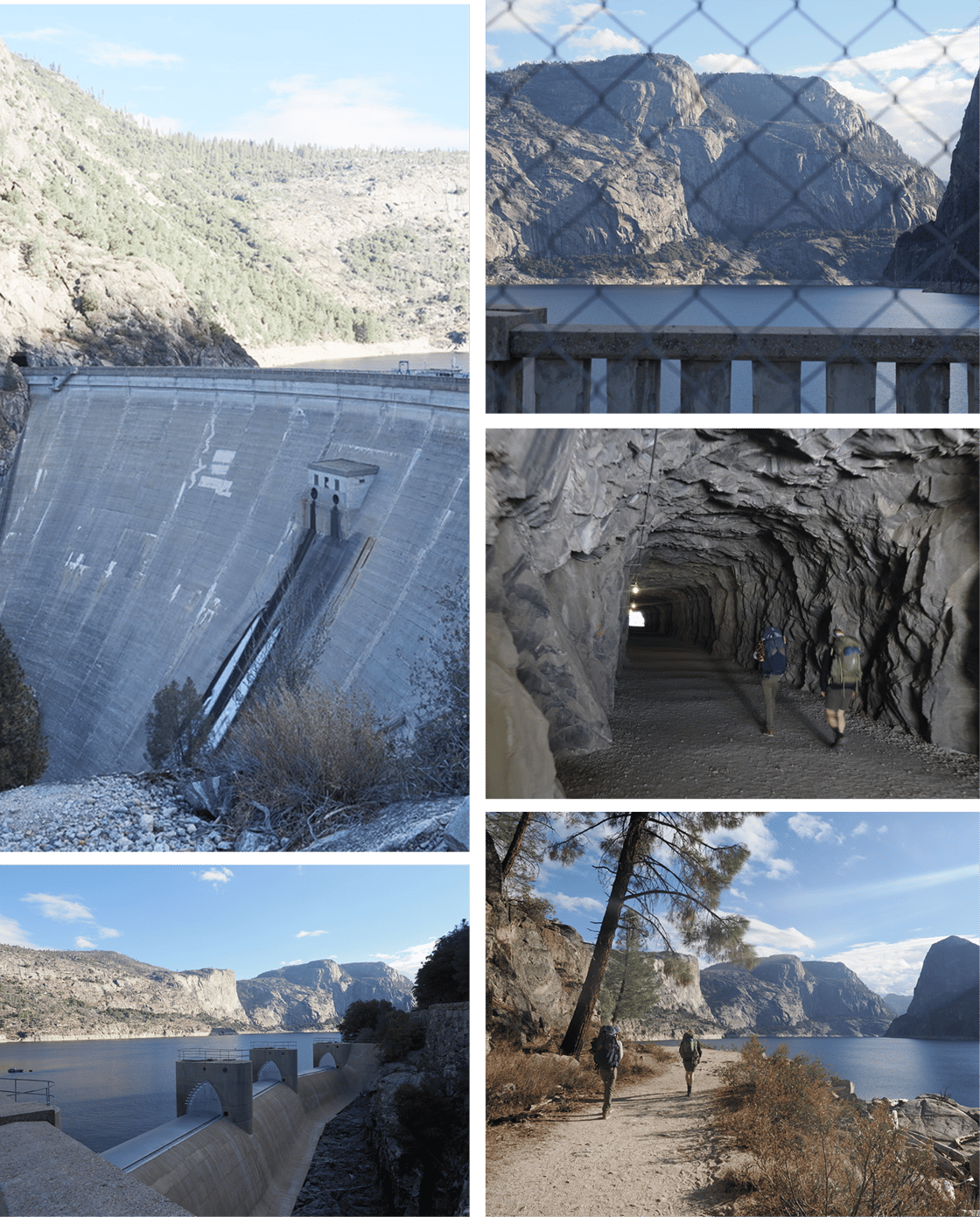

All three of us had independently heard that Hetch Hetchy is “a second Yosemite” that was ingloriously drowned by the dam. A sacrificed sister of equal magnitude. We rose the next morning to wolf down eggs and coffee and shuffled downhill to view it. It was at once both daunting and not nearly as large as Yosemite.

As we walked over the spillway and through a tunnel punched straight through granite, I was struck by the audacity of this whole scheme. The pipes from here to San Francisco require no pumping because the builders did the hard thing and drilled through mountains at a slight incline all the way. And it requires no filtration—it’s that pure. (Yes, we checked. It is treated, but not filtered.) It’s hard to imagine our society pulling something like this off today.

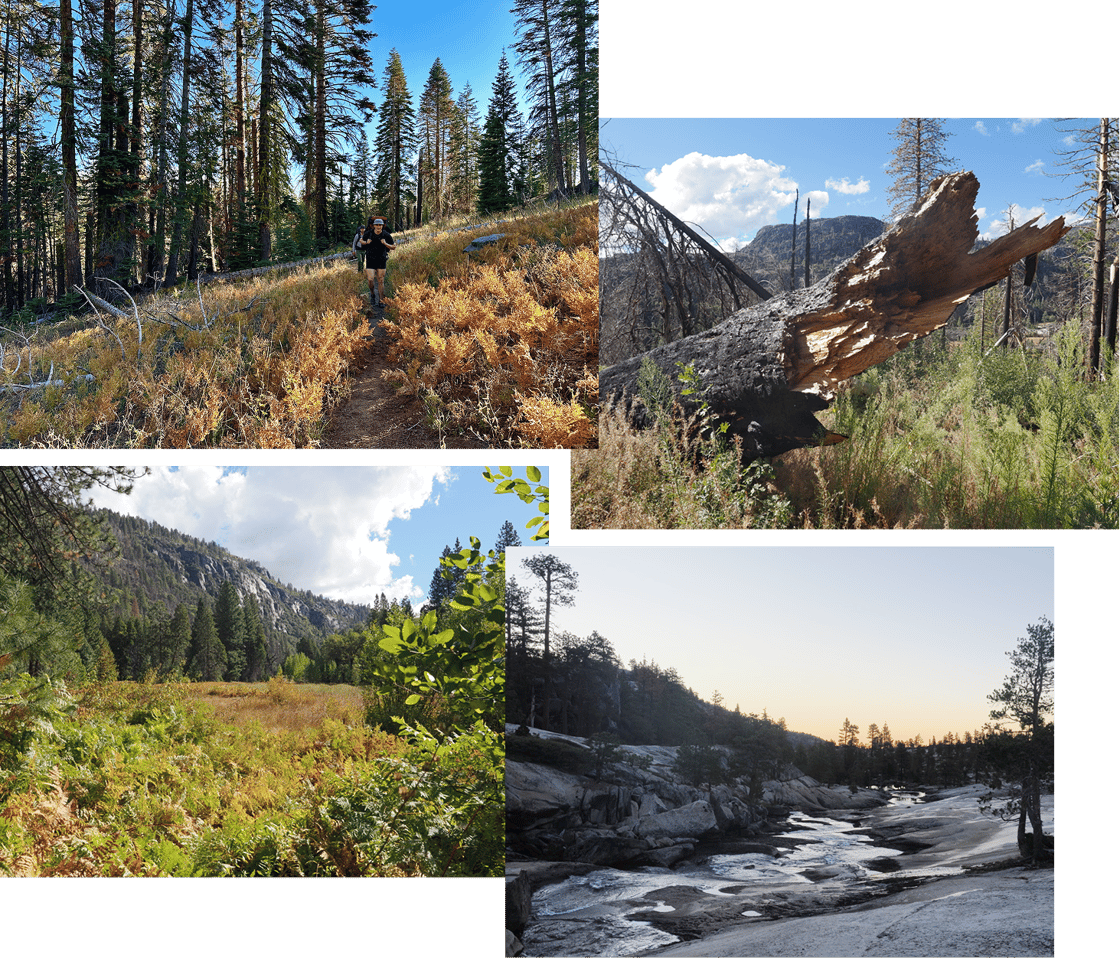

From there, it was up into the highlands for us. We were met by a rush of meadows and scree boulders and alpine shrubbery dwarfed by the immensity of the conditions at this elevation.

A song of source

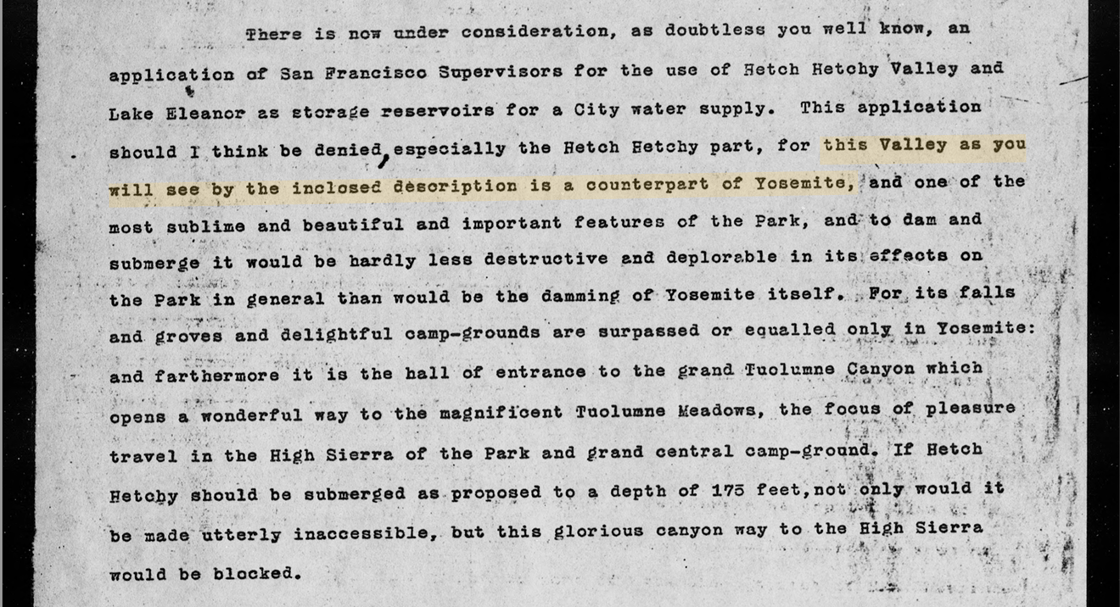

On the drive back we binged podcasts and anything audible we could find on the dam, to learn more about it, and I must tell you, the information is poor and repetitive. Everyone arguing for the dam’s removal cites the same tired statistics—and begins with that same worn phrase: “Hetch Hetchy is a second Yosemite.” After maybe the third time we heard that, we got curious: Where did that idea come from? And as our car wove back through nameless badlands around Knights Ferry, we found out. John Muir coined it in a letter to Theodore Roosevelt.

Muir fought a tireless letter writing campaign to stop the savaging of one of his favorite valleys. He died in 1914. The dam was completed in 1923. But Muir’s words survived him. The Hetch Hetchy fight gave birth to the modern environmental movement and new activist groups who coalesced to fight for legislation. The type of legislation that forces builders to pause and run studies—to hire ecologists to study local salamanders. One century later, there is a direct connection from their work to the regulations and permitting that so frustrate Ezra Klein and my architect friends.

That was plenty to think on for the rest of the drive back.

To apply this at work

If you want to make change, be a writer. Muir spent his life refining his writing to the degree where his heartfelt expression of anguish could grow into collective cultural wisdom. One person’s words are felt by millions.

The best book I read on Hetch Hetchy was Dam, which my uncle John gifted to me. He always greets me with several books under arm. Thanks uncle John.

Inspiring principle: Longview

At Fenwick, we take the long view. We produce works that compound in value and build into something greater; we paint tiles knowing they must become a mosaic without fretting whether others see it yet.

Inside Fenwick

The theme of the next issue of Rewild Magazine is “Beautiful Conspiracy.” Did you know "paranoia" has an antonym, "pronoia?" It's the belief that the world is conspiring to help you. We'll carry stories on that applied to your work.

Worth reading

The Tchaikovsky cure for depression is simple: Make art.

A+ copywriting: “News that can’t be bot.”

The Creative Cheat sheet of templates and links and such.

IDEO designers turned competitive research into a game.

Workism is making us miserable. Nobody needed this reminder but this is a thoughtful reflection on it.

The work. Curious format. This was built in Canva. Creativity is so back.

FWB Fest’s poster breaks every conventional workplace design rule and for that reason would be a great pattern disrupt at work.

Just fun copywriting. The penguins one though.

Enjoying this newsletter? For goodness sake, don't hoard. Share.