He came to us during the heatwave. Weather advisories warned of extreme conditions, and the Fourth of July had just passed. With it, the promise of fireworks and declarations of freedom and beauty.

This year, however, my dedicated summer writing time was hijacked by a sudden visit from an old friend, Steven Arroyo. Steven and I have known each other for 20 years. It amazes me to write that. Steven is the type who takes friendship and family seriously. When our lives intertwined all those years ago, it was clear then it would be for our entire lives.

Steven and I both identify as Chicanos and met through skateboarding artist friends in New York City. At the time, he was thinking of opening a Mexican eatery in the city to expand his Los Angeles empire, while I was fresh from San Francisco and trying to make it as a writer. We found comfort in our shared drive and perhaps we needed each other to remember how far we’d each come.

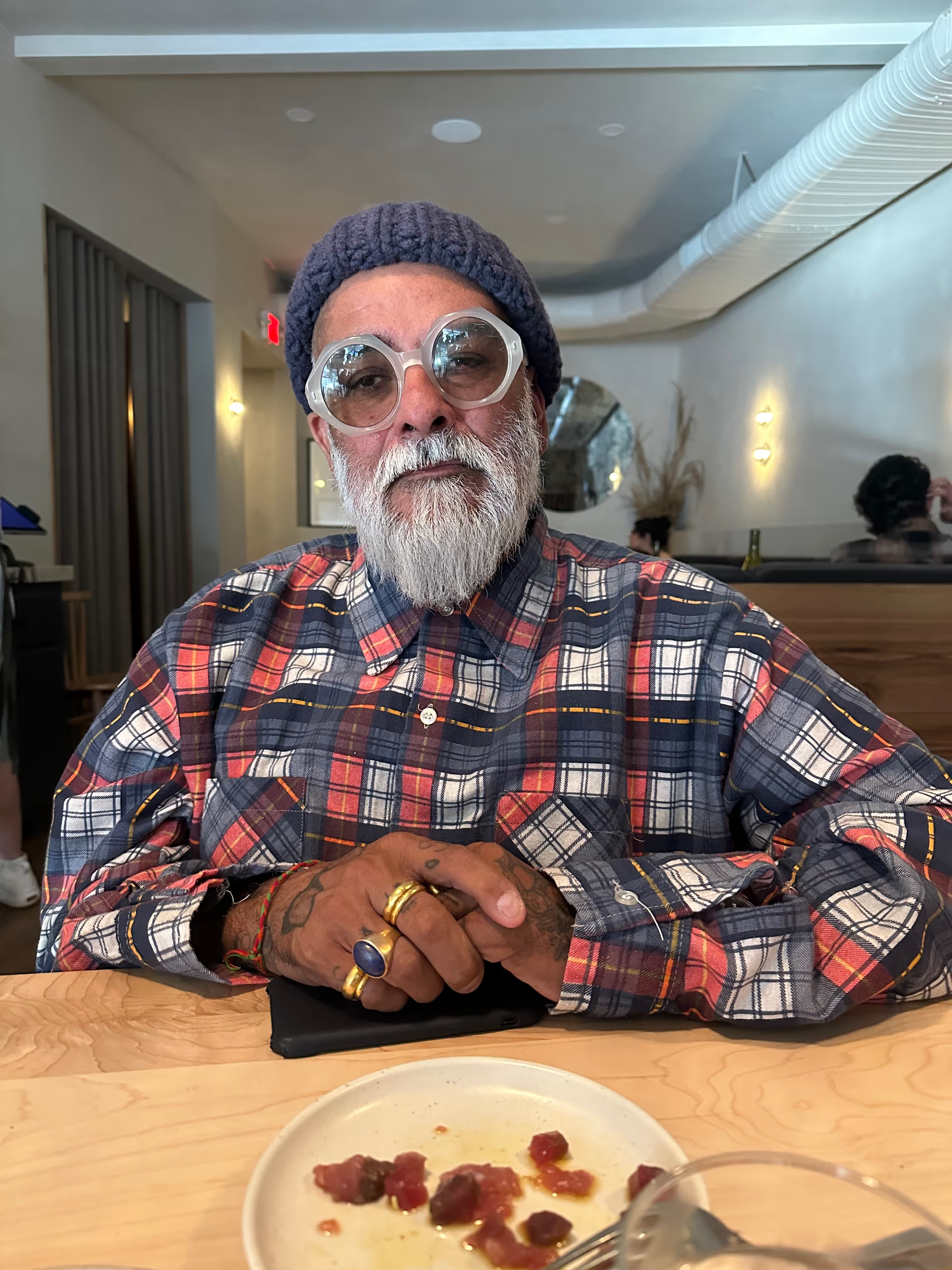

He is singular in nature. Headstrong, with a vision that is irrepressibly wondrous and colorful. He wears big hats, ponchos, and colored socks. When reaching for something, he is immediately recognizable by his signature tattoo: Ray-Ban Wayfarer frames crested on the back of his right hand; those same hands also accented with gold bracelets and stacked rings.

If you visit L.A., Steve is sure to welcome you with a meal already in progress, at a table sprawling with creative friends. He makes all his business spaces available to friends to promote their new works.

Since 1995, Steven has conceptualized and run four distinctive restaurants across L.A. without any prior culinary or business experience. He never had a credit card to his name and operated his businesses creatively if not sometimes illegally. He found ways to make things happen by any means, which usually meant making phone calls to a guy who knew a guy. Lately though, Steven’s tough-guy-who-makes-everything-happen energy has been softened by an eight-year bout with colon cancer. He’s taken to walking with a wooden cane.

Two weeks ago, he was deemed cancer-free by his doctors and this cross-country trip in a Sprinter van seems like a renewed celebration of/for life. He has plans to swim in the Atlantic Ocean, hug old friends, shop for antiques at the Brimfield Antique Flea Market, and reconnect with an ex-girlfriend. Said ex-girlfriend was seen at the farmers market in my upstate town. Hence Steven’s sudden visit. Once he sets his mind on something, he fixates.

When Steven arrives, he decides we need to walk right back out and drive to Woodstock to search for the ex. He needs to see her to convince her that he has his health back and that their connection is unmatched. I recommend we start fresh in the morning, and guide Steven upstairs to my room which has air conditioning and has been recently renovated.

The ceiling and the upper half of the room are covered by flat plywood boards to give off a Scandinavian cabin feel. Steven rests his cane on the armchair. He lets out a big sigh and slides into the duvet. He invites me to sit. He wants to talk before we go to sleep.

We stare up at the ceiling. The planks each have different patterns from the trees they came from. The ceiling is wavy and topographical. I get lost in their patterns and use Steven’s breathing as a rhythm to almost meditate. I start to feel like we are on psychedelics. Why hadn’t I ever seen all of this natural beauty in the wood before?

With my hands resting on my chest, I confide that I designed the second floor of the cottage after Rick Rubin’s Malibu house. The way the windows let the light pour in. It’s calm and welcomes the outdoors inside. Steven understands the aesthetic. All his restaurants are eclectic experiences from the moment you walk in: from the wooden paneled Spanish tapas eatery Cobras and Matadors with gallery art walls to the white-tiled Mexican food spot Esquela Taqueria with wooden shoe forms hanging from the ceiling. Each location emits notions of individualism and wonder. He’s become so noted for his unexpected restaurant interiors that he opened a design and gallery shop, Pigeon, to sell art and collectibles from around the world.

We get to talking about his dad. He didn’t have much of a relationship with him. Steven says that now that he is cancer-free, it is his time to heal and forgive his father to have more of a relationship with him, even in his father’s death. It got me thinking about my own father. Maybe Steven being here is to funnel dad energy in my direction. Maybe he is a stand-in figure for my own Chicano dad. Maybe this is the universe’s way of telling me that life is cyclical and that here in this room growth, healing, and new life can be found between two platonic friends.

He turns to face me and asks if I will write about him and the businesses he created from nothing. It feels like a heavy ask, but one that I cannot decline. “Of course,” I say. “I will write about you.” But in that moment, I am filled with a sense of looming responsibility I cannot shake.

The next morning, Steven awakens with a pain in his right side and lacks the strength to get out of bed. He asked if it’s okay to stay in bed and rest, just for today. Perhaps the intense driving exhausted him, he says. For the next three days, he barely has the energy to visit the bathroom. He barely eats. I make plates of sliced stone fruit, shrimp, and potatoes, and the plates would just get passed to the floor with one or two bites taken from them. There is a sadness there in seeing your friend’s lone tooth marks on items of food—so often the provider, now, barely able to be provided for.

I am feeling a pang of life. Age. Here we are confronted with life close to death. I watch my friend sleep to make sure he is breathing. Part of me is afraid he will die here, and the other part of me is afraid of my fear. I find myself unraveling my own assumptions. Steven and I decide to take him to the nearest emergency room. I find myself thinking about kaleidoscopic relationships, how we shift and stream into different shapes and manifestations of self. We have seen each other through two decades of relationships, business propositions, and artistic pursuits. Morphing versions of our beings. How in a kaleidoscope, a triangle can become a star, a flower, a mandala.

As Steven and I drive to the hospital, I think about what a landscape painting would look like if Steven and I—two Chicanos—painted a scene from the Hudson Valley? I like the idea of imbuing a West Coast brownness to the East Coast canon. The clouds and rolling hills would still be soft but the title would be radical in its reframing of traditional roles and norms.

In so many frames, our summer days together warrant painted portraits and still lives. This moment of stillness, life on the brink of death inching back to life, brown hands on a table, stonefruit bathed in afternoon light.

This visit from Steven is like a metaphorical portal, in which my upstate house is the wardrobe we walk through to see ourselves better. When we first became friends, there were so many things I wanted to accomplish. I had just moved to New York from San Francisco hungry for journalistic accolades. I wanted to make a name for myself and, with time, find a life partner and have a baby. It seems bittersweet now to see it from the other side.

I’ve been reading the perimenopausal novel All Fours by Miranda July. It’s a saccharine indulgence. Her persona is so outside of my own realm, but I am drawn to her desire for liberation. I’ve been in a creative rut since the birth of my son. Those nine months of pregnancy marked the most creative and productive time of my life. I birthed so many creative projects, I could not fathom slowing down or that a baby would change my priorities but it did, and the child still does. I think about work differently. I think about joy differently. I am now somebody’s mother.

In writing this, I am struck by the Hudson River School of Art and how naively and romantically those white artists painted those canyons. I love the idea of virgin spaces without the imposition of man and industries. I am struck by how many people positioned themselves and their perspectives on the landscape. We keep returning to the same vistas bathed in new light made new again by a brushstroke or new perspective.

Two weeks after Steven visits me in my country house in Upstate New York, he dies of complications from sepsis in a Los Angeles hospital. He was 55 and left behind three children. His visit and subsequent death spark me back to writing. His request of me rekindles a profound pull into purpose and storytelling as well as a means of my own healing and self-inquisition.

In our last visit together, we spoke about partnership, marriage, and parenting. He was fixated on my son and how I was balancing marriage and parenthood. It is a topic I usually reserve for female friends, but because Steven’s entire ecosystem stems from his progeny, he wanted to hear how I was building my world. In sharing stories, I heard Steven call his ex-wife his wife. They still spoke daily and referred to each other as life partners. Steven placed the ultimate value on co-parenting. From this interaction, I learned that I had been holding on to an outdated notion of partnership and that Steven’s visit opened up the aperture for change.

.avif)

The Mexican-American author Vanessa Angelica Villarreal writes, “Fantasy is an act of imagination; to recall a memory activates the imagination; history is a collective imagination. Where is the line between fantasy, memory, and history if each is set in an imagined past?”

I did not know then, but what Steven and I were doing together—in our talks—was rewriting our pasts. We were changing our cellar memories to heal ourselves, and in the recounting of stories, we had been admitting and releasing guilt to change the fabric of our beings. He gave me permission to be free, to be uncategorized, and to be unscripted.

After his death, I took up writing daily and spent the next five months working on a novel I’ve titled The Hudson River School of Painting and Unpainting. I think of the remarkable last visit and am so thankful for the exchange. It helped me identify my new path. I began to understand that my imagination is my liberation. It helped me free myself from restrictions.

Steven and I are once again overlooking the Hudson River at sunset. We have come far from where we were from. We take in these vistas and re-imagine how we can make them our own. I begin to write about re-imagining the past to write my future.