My friend Mag recently convinced me to drive up the California coast to plunge into the freezing water and swim out past the waves.

There, terrified, we dove, and followed the kelp down, down, down, to twist spiny purple sea urchins from the volcanic rock. I considered this frigid ordeal a form of respite, actually. I think most people of conscience would, the way the world is right now.

The news is all so wretched, yet the brightest of our generation hunch over MacBooks just trying to make car payments. We’d be activists, but for our contracts; always renters, never owners. We’ve so many lustrous electronic wonders to enjoy, but alas, the online world we’ve inherited feels like hell but with nicer UX. It’s an infinite strip mall of ad-fueled opium dens and boosters peddling apocalyptic nonsense. And we can’t look away. No wonder so many smart people I know feel paralyzed.

It is in this world that Magali Charmot, Mag for short, cuts a striking figure. She has a personal practice for transmuting the news, which demotivates the rest of us, into art. Right now, she’s focused on the great trophic die-off happening quietly beneath the waves along the entire Pacific Rim; San Diego to Alaska, marine critters are expiring. Our tidal pools have grown tidier and this should scare us in the way a baby’s silence is scary.

I was curious what spurs Mag to such gleeful action while confronting the topics that so destabilize the rest of us. What I’ve found over dozens of breakfasts and on our trip is that there is something in the Mag approach that allows her to metabolize strife into art. I believe there’s a lesson here for anyone who wants to deliver themselves from the jaws of depression, as Mag once did.

That’s how pearls form

Mag’s short blond hair falls at a rakish angle that she leaves tousled. She resonates very much with the neopunk aesthetic, often in denim, slender arms, and many rings. She has a ready laugh, and when it comes on, she looks to the side. There is nothing you can say to Mag that doesn’t elicit her interest. I know because the breakfast club we share in downtown San Francisco is a menagerie of personalities, and she is never short of conversation. She’s an eager listener and grows larger in dialogue. Say something off-putting and she’ll consider it, always with that sideways laugh.

A big topic at these breakfasts has been the creative Armageddon—a third year of scything layoffs and agency die-offs. Oftentimes, there’s a group of us. But sometimes it’s just Eve, Mag, and me, thinking as the rain drubs the windows of the hotel restaurant.

Mag is up to much more than she lets on and she thinks in oblique channels unavailable to me. “I’m writing a book about purple sea urchins from the lens of appetite,” she’ll say. Or she’s working on a personal finance brand, or an ‘installation.’ Or she is, we have learned, helping to rebrand her son’s school—which she admits with the laugh of someone who knows the pain of helping the uninitiated appreciate high design. She’s studying semiotics. She’s attending secretive artist dinners in the woods. Philosophically, she will go there—anywhere—and she liberally donates the credit. “Awe is a mixture of surprise and fear,” she was saying recently. “There’s a guy at UC Berkeley, Dacher Keltner, who writes about the science of awe and how people are more likely to change their mind after experiencing it. Awe makes them more flexible and adaptable.”

There’s something primally activating about awe, she explained. “It intimidates people into being honest. People in his study were like, ‘Oh my god, for the sake of my own mortality, I see it now.’”

"Awe is a mixture of surprise and fear."

Mag was not always so active or upbeat. She was once an art major who took the ‘starving artist’ oath to poverty before she recanted and took a job in advertising. Naturally, she made less and less time for art. The work was exhilarating. But also draining. It became everything. Then several family members grew sick and she fell into a depressive crevasse from which she couldn’t climb out. “I was suddenly having to deal with a lot of grief. It was a real dark place. I remember thinking, well, my mind will survive this, but I don’t know if my body can,” she recalls, “which is a weird thought, but it was just … wow, the pain. To escape it I thought, ‘I’m going to find a job that literally eats my entire life,’” which led her into a role traveling six months of the year doing ethnographic work.

Research carried the simulacra of creativity and dulled the pain for a long time. But the horrors lurked offstage, and eventually she felt the desire to make another change. A therapist pointed out that she kept referring back to a time when she made art. That it used to be a big part of her life. “Well, sure, but I’m not an artist,” she found herself saying. The title felt daunting and unearned—but perhaps she was telling herself this because she wanted to return to it so badly. Awareness bred desire. Desire became action. “My therapist gave me permission to go back to it, and once I realized the effect on my mood, it was just like, yeah, I can deal with the pain. Because now I could materialize it. I could get it out of my system.”

“It was just like, yeah, I can deal with the pain. Because now I could materialize it.”

This is how art became a part of Mag’s life too important not to keep. She committed to doing 80% work, 20% personal art, and joined a collective of friends who put on several shows a year. She partook in huge, intimidating installations like 60-person-long table dinners. It was as if lights were winking back on in the garden of her soul. She shifted the balance to 60% work, 40% art, and each ratchet was a new rush. “All of a sudden it was really, truly fulfilling,” she recalls. “It all came to me through that art collective, getting together and talking concepts. It felt like, ‘Are you kidding me? This is the best time ever!’ I promised myself I would never stop this practice.”

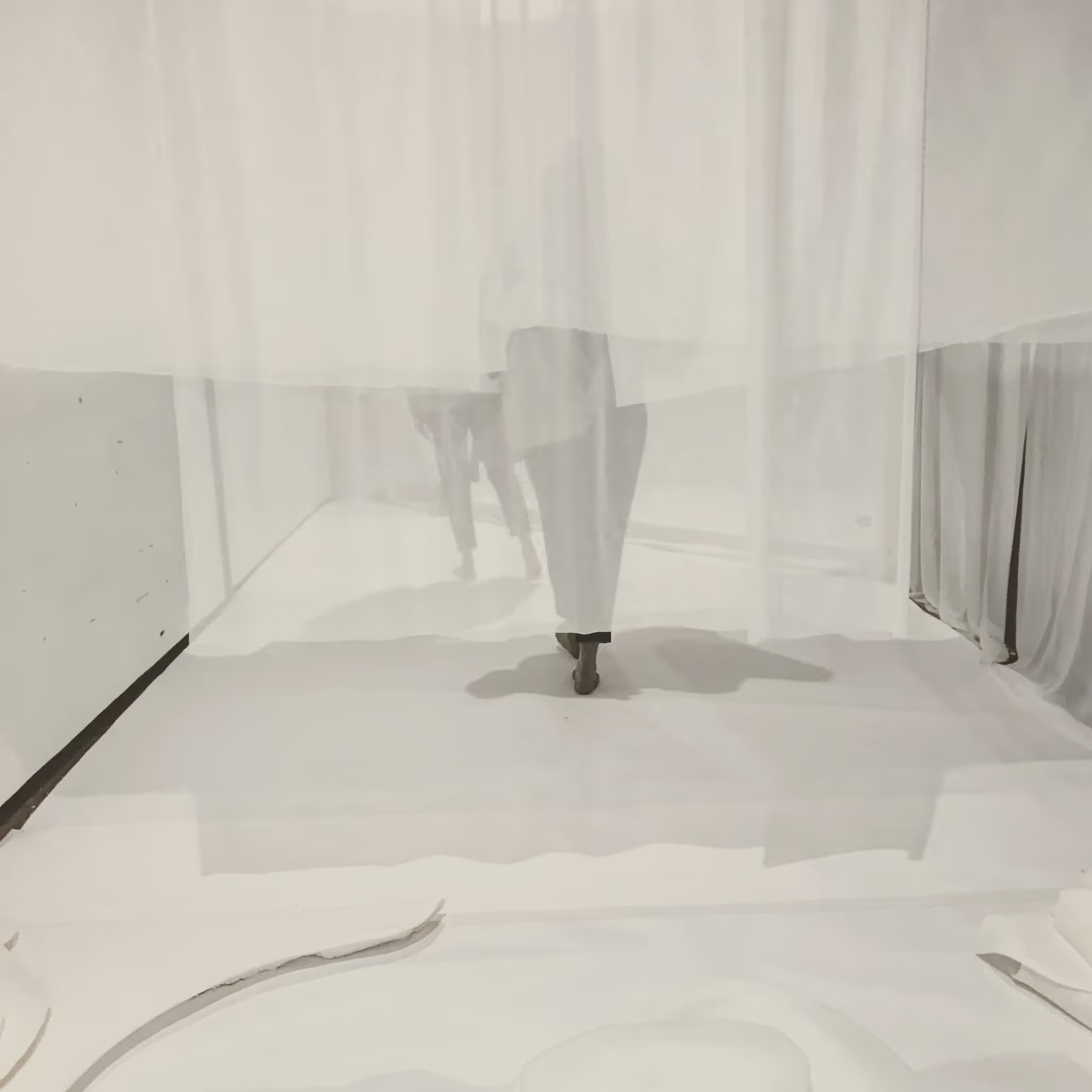

One show they put on—”Le Corps Poétique” (The Poetic Body)—cemented it. Her favorite installation in that show conveyed the notion of a threshold, or a portal between one place and another, divided but open. The art collective built an entire building within a warehouse, which had two sides, separated by a door. One side was entirely white and full of ethereal shapes. You had to take your shoes off to walk around on fake snow. “It was liminal to get to make yourself and others think about your own sense of existence,” she gushes. “It was immersive, symbolic, probably one of the best experiences of my life.”

In that prior dark period, when the job ate her life, Mag had a recurring dream. She didn’t think much of it. But now the dream started to transmute.

“Every night I’d awake in this sort of prison where everything was outside my control, rife with disease and grief. It was purgatory,” she recalls. “It wasn’t terrible, but it wasn't great. And you’re just stuck there. The worst part is, I could hear the outside world—a summer at the beach, laughter and sun and happiness, outside the door. But I was stuck in this dark room. Then one day, for some reason, I don’t know what triggered it, I tried to push the door open and was like, ‘What the fuck?’ Because it opened. The entire time I had been dreaming this, I'd never tried to push the door.”

She turned that dream into an art piece called Primal Catastrophe, about birth: About a child coming to the awareness that they are not the same as their mother, and being expelled into the mortal, living world.

“So yeah, I guess you could say those kinds of moments now always translate into art pieces,” she says. “But also, to your question, I think that's how I think of pessimists. I think they never just tried to open the door.”

"The entire time I had been dreaming this, I'd never tried to push the door.”

The plunge

The Northern California coast is a tumult of sandstone and basalt plunging into a merciless sea, which gleams as it hammers the rocks. This space is austere. Driving up, it feels empty, and perhaps that’s increasingly so. Warming temperatures have caused a great die-off beneath the waves, and the trophic column of predators have all been eradicated—which has left one tiny resident to wreck the ecosystem unchecked: the spiny purple sea urchin. These critters have multiplied in the billions and, like a bed of razors, have gnawed through the roots of kelp plants from Mexico on up to our destination, Caspar, California, and far beyond. The kelp are our coral reef. Without them, much else can, and is, dying.

Fenwick’s co-founder Eve and I are both drawn to Mag’s sense of mission, and because our visitors that weekend are too. My sister Lauren and her husband, Robin, are both microbiologists. Their visit from France coincided with Mag’s rally to go harvest urchins—and her message to fight back against what man hath wrought struck a nerve.

But. Go harvest urchins. Intellectually, I know this means diving, so I rent a 7mm wet suit and fins as instructed. Though a piece of me is terrified. I know the brutal cold of the California coast from surfing, and it has never in my life occurred to me to try to leave the board and touch the stony bottom. Wouldn’t we get thrashed? Raked across sharp rocks? “How much weight do you want to carry?” the dive shop guy asks, holding up a 20 pounds of die-cast lead. “Must I?,” I reply.

The drive up is a pastoral vision. We stop for roadside barbecue in a grove of towering Sequoias, and exchange the city air in our lungs for the smell of pine and sap. By late afternoon, we arrive at the sandswept asphalt lot before a campground and there Mag and group are walking to don wetsuits. I rush to our cabin. The only way I can scuttle into my 7mm neoprene armor is by lathering myself in water and hair conditioner. I pull the chin piece up with a slap. When Eve finds me, she doubles over in laughter and, kindly, escorts me to the beach.

The surf is intense. If it gets bad, I can always turn around, I tell myself. Robin takes photos and Lauren and Eve advise on strategy. High on the beach, I don fins. “You put those on in the water,” shouts a passerby. The group assembles, and the swim out is more difficult than I’d feared—I bob in the shallows pulling at my fins being pummeled by waves. I turn into the sea and inhale faceful after faceful of brine. The winds pick up and it’s now everyone for themselves. My nasal passages burn and my awareness shrinks to the emergency ahead. I keep swallowing seawater until I’m gagging and exhausted. But we all persist. Past the breaks, we reach clumps of kelp—their long stipes tug at our legs. Mag is thrilled enough for all of us, and calls it out—one by one, we dive.

But. Are the urchins ten feet down? Twenty? I don’t know. I’m suddenly embarrassed to realize that I don’t understand how light works underwater. From the surface, I can only see as far as my fingertips, so I dive blindly into swirling particles. My eardrums shriek. Nothing. Nothing. Then a sunlit panorama opens—sharp rocks layered with gleaming purple urchins. How does the light penetrate this far? I’ve no idea. I rip and twist one small urchin from the rocks, and the current tugs me askance, and I surface frantically. Others do too, holding their catch. We pile them in the kayak. Every haul is invigorating; over the swells, we call out promising locations. There are millions of urchins. Many are weak and in a zombified state for lack of food. Some are smashed because divers already swept through with hammers.

Our eardrums weary and throb; we’re trashed into a stupor. Some stretches, I just lay comatose on my back, looking up into the gray. Eventually the call comes, we’ve all had enough.

On the beach, I am so dazed, and Eve has to escort me to the showers. Everyone shares food and fire and reflects on the urchin pile that someone has now counted—380. Here under the stars, this lonely troupe that chose to make the trek, each shares why. There’s something in the doing that’s an antidote to thinking. We gather ourselves for one final feat—the smashing.

Our group heads back early the next morning and we see Mag and her crew headed out again, irrepressible, excited, in awe at the power of the ocean and at having mastered its depths.

“The fact we were together was a huge piece of it,” she recalls to me later. “I went out with such low expectations, and it was so intimidating. I’m a good swimmer, but out in the Pacific, tangled in the kelp, it’s just so alien and strange, right? I loved how we all motivated each other and came back so proud, like kids. I honestly had to decompress the week after, because going out and doing something so primal was a high I had to come down from.”

She pauses, and thinks. “When you experience that in nature, just like art or religion, you take that into your life, and that changes you as a person,” she says, smile brightening as she relives it. “I definitely felt the fear, the awe.”

“When you experience that in nature, just like art or religion, you take that into your life, and that changes you.”

The only sense to life is what we make of it

Mag does not believe life happens for a reason. However beautiful, she doubts it’s some cosmic conspiracy. “I think people make up the reasons in hindsight,” she says. Instead, Mag believes in the doctrine of doing. Of making as a practice of transmuting. Of seeing what you hope to shift in the world and not asking why others aren’t doing it, but to just start on your art.

I ask her where this comes from.

“I’m a born optimist but not naive,” she says. “My optimism helps me look at the world in a certain way. The world can be a harsh place for sure. But I am pretty readily convinced there is a way out, or a solution, or a million other options. Whenever I face a challenge, that's my first thought: ‘There’s probably at least five ways to solve this.’ I’m not sure that’s confidence. That’s just a belief.”

Whatever the source of the belief, it seems an antidote to paralysis. It allows Mag to take in all the same wretched news as the rest of us and metabolize it into something beautiful. It is, I believe, no coincidence that the name “Mag” is, at its origin, Greek—margaritári—meaning “pearl.” And pearls are the product of a creature transmuting an irritant into a brilliant, ovoid mirror that reflects our world back to us, brighter.

Mag attended an artist dinner weekend recently. This time, she brought her four-year-old son.

The speaker addressed everyone as “artists gathered here.” Her son turned and whispered, “Mommy, are you an artist this weekend?” Her friend leaned in and answered for her: “Yes. Your mom’s an artist. And a really good one.”